review: marie antoinette

November 23, 2006

You might say that Marie Antoinette isn’t about all that much. You would be correct, of course, but that misses the point of the film: Marie Antoinette gives us revisionist history in pictures–exquisitely crafted pictures–from which we gain a brief, impressionistic glance into the world of a very young and impressionable girl who just happens to be the next queen of France. With consciously hip pop tunes to ferry us through its tableau of incredible excess, director Sofia Coppola creates a stridently modern and deeply personal take on love, loneliness, and the perils of growing up.

Much of its power derives from the narrative’s singular focus on Marie: her nervy awkwardness on first meeting new husband Louis-Auguste (Jason Schwartzman), her growing delight in the fanciful frivolities of life in Versailles, and her deepening anxiety about, as she says, “letting everyone down”–we see it all, but only in fleeting glimpses, as when cinematographer Lance Acord’s camera follows her into her bedroom, where the smile she puts on for the world cracks as she begins to cry, her pale face, tinted luminous golden-red by the light from the window, commanding the frame for several long seconds; the next shot finds her seeking solace in a new pair of shoes. Marie Antoinette is full of such little moments, and each one elicits a sigh of appreciation for how utterly perfect it is, all by itself.

In between them, we are treated to perhaps the most visually luscious production design ever conceived for a film. Granted exclusive access to film at Versailles, Ms. Coppola spares no detail (and surely no expense) in reproducing courtly splendor in all its charm, beauty, and ugliness, from untold mountains of pastel-hued confections to sumptuous costumes, gilded furniture, and outlandish performances. “This is ridiculous,” Marie quips, exhausted by the interminable demands of “propriety” surrounding the use of all this magnificence. The response? “This, madame, is Versailles!”

But all this beauty would be as nothing were it not for the grace of Kirsten Dunst, whose distinctly American beauty feels (strangely) at home in this streamlined, fictionalized account of events. Perhaps Marie ought to have be French for the sake of “authenticity,” but, recalling the ease with which I empathized with the myriad expressions which played across Ms. Dunst’s face throughout the film, perhaps it is that commonality of kinship which makes her protrayal so accessible and so delightfully familiar. It is a great strengh, I think: this is not a French film, and Ms. Coppola is not French (neither am I, though I wonder how the French have received the film). Nor is Jason Schwartzman, Ms. Coppola’s cousin, who plays Louis, a short and taciturn king-to-be, with such a blissful air of aloofness that we almost don’t take him seriously. Almost.

In fact, Schwartzman grounds the film with a performance that is both understated and, at very special moments, utterly hilarious (I defy you not to chuckle when, after ordering aid to the Americans, he picks up a rolled-up map and begins peering through it intently). The sisterly affection that Marie develops for him is both touching and ironic, as their non-romance fizzles badly–they share a bed, sleeping on opposite sides despite her repeated advances (they need an heir, you see)–and the dark circumstances surrounding the film’s conclusion provide ample evidence for his nobility, standing proudly as he does in the dark of Versailles while a pitchfork-wielding mob rails just outside.

Excellent also is the extensive supporting cast, from British comic actor (and personal favorite) Steve Coogan’s wry turn as “Ambassador Mercy,” to Rip Torn’s pompous, grandiose Louis XV, to the button-cute Lauriane Mascaro’s two-year-old Marie Therese: each has a part to play in this swirling array of color, laughter, gossip, and eventual decay.

And decay it all does, though the film spares us the nastiness of the royal couple’s gruesome end. Rather, it closes gracefully, a peaceful carriage ride giving us a farewell glimpse of Versailles in the fading light of the evening. In one instant, Marie leans forward; her face, previously a deep reddish-orange, is suddenly a blindingly bright white in the sun; seconds later it is gone. Would that I had had a camera to record that frame for posterity, I think now. Such great beauty is frightfully rare.

–D. S. W.

review: casino royale

November 20, 2006

It’s not just a Bond movie, not just an action movie: it’s an honest to goodness movie movie. Yes, rescuing the franchise from the plains of camp is a whole new take on the iconic character, an origin story in the style of Batman Begins that gives British actor Daniel Craig free rein to show us just how cold, menacing, and ruthlessly efficient James Bond can be while deepening our conceptions of his vulnerabilities and uncertainties. While not entirely forsaking the series’ trademark formula of girls, gadgets, and improbably large explosions, Casino Royale begs you to take it seriously as it goes about spinning its tale of intrigue. And so we do.

Without demeaning Pierce Brosnan’s version of Bond, his was always more superman than man, traipsing around exotic locales with shirt strategically ripped and face cut just so: it screamed “hero,” but seldom were we meant to feel that our superspy was ever in any real danger. The brutal fight that opens Casino Royale immediately erases any memory of that fantasy, with Craig fighting for his life in gritty, washed-out black & white; he succeeds in his errand, of course, but that, his first kill, establishes this Bond as one unafraid, even eager for the unpleasant and dirty business of defending queen and country. Acutely uncomfortable scenes of torture and poisoning hammer the point home further: no “nice guy” could survive as 007, and James Bond is no nice guy.

He does, however, have a soft spot for women, in particular Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd, a disarmingly attractive agent of the French Treasury. Ms. Green, best known for her role in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, holds her own against Craig’s commanding presence in their many shared scenes, playing a character both powerful, as in her formidable exchange with Bond on their first meeting, and fragile, as when she lies, quietly weeping, under the jets of a hotel shower after a harrowing escape. Their relationship has subtlety, passion, and even tragedy, a far cry from Mr. Brosnan’s supremely assured seduction of Rosamund Pike in 2002’s Die Another Day, a dalliance that ended as carelessly as it began. No, Vesper means something to Bond, and I get the sense that their relationship will continue to influence the character going forward.

Also mezmerizing are Mr. Craig’s steel blue eyes, which radiate with alarming intensity that director Martin Campbell uses to quiet effect in the mostly thrilling high-stakes poker game that is the film’s dramatic centerpiece. Built, brief, and impeccably attired, he strides about with a touch of arrogance justified by how dangerous he seems. So too does the terrific Danish actor Mads Mikkelsen’s Le Chiffre ooze the sort of squirmy desperation that any good Bond villain must, though (refreshingly) this one’s plans don’t quite stretch to the usual “world domination or bust.” Instead, he’s a mathematically-inclined banker to terrorists with an iron will and a serious bone to pick with Bond, whose meddling has cost him dearly. Frustratingly, however, the expected climactic confrontation never takes place, the action instead shifting to a “shocking” betrayal and lots of shooting in a collapsing building.

The action is, incidentally, first-rate as always, from the aforementioned opening to a kinetic chase through a construction zone to a stunningly choreographed multi-stage foiling of a terrorist plot in and around the Miami airport (jet fuel + bombs = a good time). With the best stunt people that money can buy, sitting back and watching it all unfold is a genuine pleasure, albeit one without the putative delights of car chase this time, sadly, as Bond’s custom Aston Martin DBS crashes in an eye-rollingly ridiculous fashion–seven full revolutions–seconds into a high-speed pursuit; the built-in defibrillator and weapons cache sure do come in handy, though.

Unifying the film is the work of editor Stuart Baird and cinematographer Phil Meheux, whose experiments with eccentric camera angles, quick cuts, and brilliant close-ups are consistently engaging even when the film drags a bit in its middle sections. Pacing is certainly a problem at times, admittedly, as the story progressing in fits and starts with action sequences liberally sprinkled throughout. The actors’ fine performances more than make up for any failings, though; this reborn Bond is full of surprises and ready to put its sometimes-embarassing past behind it. Now isn’t that nice?

–D. S. W.

it’s the phoenix teaser!

November 19, 2006

See it below, thanks to YouTube. An official version will be out tomorrow.

–D. S. W.

review coming soon

November 18, 2006

This evening I will be taking in a screening of the latest Bond flick, Casino Royale, a film which has garnered impressive reviews from critics across the country. Can it make me forget the awfulness of Die Another Day. With a new Bond and a new look, it just might–look for a review tomorrow. This next week I should also be able to see a few films I have been meaning to see, including Marie Antoinette, For Your Consideration, Babel, The Prestige, and perhaps Volver or The Departed. Things really have been too busy lately.

–D. S. W.

the phoenix alights

November 18, 2006

Quite a bit of Order of the Phoenix news to report today. Those of you interested in seeing the teaser trailer immediately should run (not walk) to your nearest multiplex for a screening of Happy Feet–the trailer is attached. Those of you uninterested in a movie about talking penguins will have to wait until Monday, when the trailer will debut on the Happy Feet website at 12:00 p.m. PST (3:00 p.m. EST). In the meantime, ComingSoon.net has a bevy of newly released official photos from the film, viewable here (my favorite is below). Finally, the new (and creepy) teaser poster is viewable here. I must say, it does look rather exciting.

–D. S. W.

is this progress?

October 15, 2006

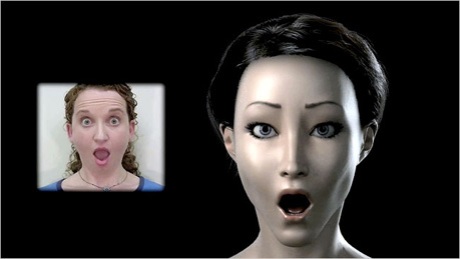

The Times recently ran a story profiling a set of technologies under development at a Santa Monica startup called Image Metrics that purports to offer a lifelike means of creating virtual actors and performances for film, videogames, and more. Though motion capture, the process of recording a performance based on marker dots placed on an actor’s face, has long been available, the company claims that their software goes beyond this by replicating eye movements and other subtle facial details that, collectively, can make a virtual actor seem “real.” Chairman Andy Wood calls it “soul transferrence.”

They have certainly convinced Hollywood correspondent and article author Sharon Waxman, who writes, “Ultimately, though, Image Metrics could even go beyond the need for Tom Hanks — or any other actor — altogether.” Bold words, indeed. While the demonstration provided in the accompanying video (see the link above) and the potential applications mentioned by convert Taylor Hackford (director of Ray and other films)–allowing actors to “play” younger versions of themselves; bringing dead actors back to life to share scenes with modern ones–are undeniably intriguing, I have significant reservations about its implications.

According to its web site, an early version of Image Metrics’ technology powered the 2004 animated feature The Polar Express, a film that, more than any other, exemplifies the phenomenon known as the “uncanny valley.” Current animation techniques allow for creations that are almost, but not quite, identical to real actors. I say almost; the gap between the best artificial creations and actual reality can come off as disastrously eerie if it becomes small enough, as it did (sort of) in The Polar Express–many critics derided its animated characters as “disturbing” and “doll-like”–and as I fear we may see in the products of this new iteration of the technology that Image Metrics is promoting, no matter how much more “real” it is.

Simply put, until the dawn of animation that is practically perfect–read: absolutely indistinguishable from reality–I, and much of the moviegoing public I think, have little use for digital actors that are incrementally more evocative of their mores substantial counterparts. It is the same problem that, to a lesser extent, afflicted the Star Wars prequels, whose overenthusiastic author eschewed physical sets (and even actors) for the immaterial creations of Industrial Light & Magic, and that cheapens visually ambitious upcoming “next-generation” video games such as Crysis and Alan Wake. Mr. Hackford’s examples too, for all their promise, sound more like a silly hypothetical construct than something that consumers (and film buffs) would care too see in a multiplex of the year 2015. It smacks of technology being developed and used for its own sake, which effectively renders it meaningless.

Yes, what is most distressing here is that there is no apparent necessity for any of the avenues of possibility that the Image Metrics tech would offer. VFX has been, at least until now, a means of creating visually fantastic backdrops for human drama–that’s human, as in “consisting of non-artificial people.” Unlike, say, squadrons of TIE fighters or glowing laser-swords, ordinary human actors need no magical help in representing themselves as they are, and thus the search for a replacement for them is a puzzling choice of endeavors. Doubtless there is money to be made, but even if it succeeds, I am very much inclined to ask, “So what?”

If this is progress, count me out.

–D. S. W.

coppola scores with critics–again

October 14, 2006

Overcoming a disastrous reception at Cannes last May, Sofia Coppola’s second feature Marie Antoinette is garnering respect from critics, or at least from those fortunate enough to see it this weekend at the New York Film Festival. A.O. Scott of the Times calls it “not so much a psychological portrait as a tableau of mood and atmosphere,” one filled with “lovingly composed and rendered images,” while David Edelstein, writing for New York Magazine, praises it as “one of the most immediate, personal costume dramas ever made.”

I have long been looking forward to it, both because of Ms. Coppola’s amazing success in her 2003 film Lost in Translation and because of the eclectic ensemble cast headlined by Kirsten Dunst and Jason Schwartzman (as Louis XVI) and also featuring, among others, the delightful Steve Coogan, of Tristram Shandy and 24 Hour Party People, and veteran character actor Rip Torn. The film opens wide next Friday, October the 20th, and you can count on a review from me shortly thereafter. Do go see it yourself as well, won’t you?

–D. S. W.

review: flags of our fathers

October 12, 2006

Clint Eastwood is a famous actor and respected director, but he also has a more subtle–and, arguably, underrated–talent for musical composition. For his last two films, Mystic River and Million Dollar Baby (both Best Picture nominees), Mr. Eastwood has insisted on composing the sparse musical accompaniment himself, a practice whose dividends continue with his most recent project Flags of Our Fathers, a World War II epic that tries and succeeds, mostly, in carving out for itself a niche in this overcrowded genre that saw its most complete expression in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan not so many years ago.

For better or worse, Flags is strongly reminiscent of that film for much of its running time, offering up the same grisly imagery, disconcertingly disorienting soundscape, and thoughtful meditation on the morally clouded and painfully human aspects of its “heroes.” And indeed, it is the very concept of the hero that Flags works to explore, and ultimately to dispel, at least in objective terms.

Revolving around the iconic moment captured in Joe Rosenthal’s 1945 photograph “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima,” the eradicates any romanticized notion of the flag-raising as a courageous epitomization of American patriotism by revealing its less-than-savory exploitation by a government eager for some good news. The three surviving members of that motley crew are shipped back to the States for a shamelessly dumb tour of the country in a desperate attempt to raise $14bn–“that’s billion with a ‘b’!”–for a dangerously depleted military.

These three men, the proud yet sullen American Indian Ira Hayes (Adam Beach), the nervous and eager-to-please Rene Gagnon (Jesse Bradford), and the stoic and wounded John Bradley (Ryan Philippe) are the lens through which we view the drama. They bicker, doubt, and are disgusted at what they do in service to the political machine, perhaps even more so than at the horrors they left dead or dying on the black sands of Iwo Jima, and in this they serve as a proxy for the viewer, though one sufficiently removed as to spare us the unspeakable sorrow that each carries with him.

This is not to say that the film is uninvolving. While the battles can be exhausting at times, the welcome appearance of the score’s simple melody, developed on guitar and piano, is sufficient to imbue the scarred vistas of the island with a kind of poetic resonance. That potency is heightened when the camera closes in tightly, as it does at the most appropriate of times, on one actor, time seemingly suspended as grim determination washes over his face, as when John, his silhouette in inky relief against the brightness of a cave opening, peers in to glimpse the gruesome fate of a fallen comrade (a sight that we do not see). To witness his strange mix of fear, anger, and sadness is to glimpse the emotional heart of Flags of Our Fathers, to begin to understand the extraordinary effects that mortality and brutality can have on ordinary people–which Ira, John, and Rene most certainly are.

Rather than telling the story chronologically, Mr. Eastwood makes the risky decision to recount it via numerous flashbacks, the frequency of which increases as the film goes along. It works, mostly, though certain transitions come off as clumsy and others rob us of our connection to a particularly riveting scene. All is forgotten, though, with such a dazzling image as that of Ira, drunkenly slouched over in a hotel room chair, imagining that the violent thuds and bright flashes of the unruly weather outside his window are instead the ominous signs of mortars and flares. And so it is, as we move into the past with Ira, huddled in the crags of a godforsaken hill, pulse racing as he calculates his next move.

It is in moments like these that I see the depths of Flags‘ respect for its subject matter and, more significantly, the reach of Mr. Eastwood’s ability to humanize, without pretense or agenda, what might otherwise be a rather ordinary, though competent, dramatization of the book from which it derives, a book written by James Bradley, son of John, as a response to the memory of his father and the stories he gathered in his interviews with survivors of the war. Writers Paul Haggis and William Broyles Jr. elegantly frame the film with an intimate portrait of that writing process, anchoring it with beautifully lit snippets of conversations and a poignant coda between father and son.

Over the final scene, one that might inspire joy if not for all the harsh realities that surround it, the film returns to its thesis on heroism, spelling out precisely–and also somewhat heavy-handedly–what is more than obvious by then: that the mythical status we lavish upon a certain few is incomprehensible, even unacceptable, to its objects, people like John, Ira, and Rene who, as they say, “just happened to be there at the right time.” Yet its necessity is surer than ever, because, despite its lack of substance, it can provide boundless optimism to those who bear witness. And in such a dark time as during World War II, optimism is a rare commodity.

It is not an especially original conclusion, I must admit, but it is a genuinely American one, suiting Mr. Eastwood’s restrained style of storytelling most excellently. The same might be said of the film itself, and so I do: it does as it sets out to do, and its flaws, though glaring in the moment, are swallowed up in the wistful contemplation we are left with when it ends.

–D. S. W.

review coming soon

October 10, 2006

As I have just returned from an early screening of Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers, I hope to have a review up tomorrow evening (likely rather late, as these things go). Do check back then, won’t you?

Update: My schedule being as it is, look for the review tomorrow (Thursday) instead. Sorry for the delay.

–D. S. W.

trailers, or how to spend your free time

October 5, 2006

Today, ladies and gentlemen, I have for you an hors d’oeuvre tray of tantalizing delicacies from to sample. First, Christopher Guest’s upcoming mockumentary For Your Consideration, which features longtime collaborator Eugene Levy and a diverse ensemble of talent both new and old. Ricky Gervais (!) is in there as well. The trailer is good for a few chuckles, sketching out the zany plot which depicts the making of an independent film that is afflicted suddently with Oscar “buzz.” How exciting (at least, I think so). See that here.

Next, director Ed Zwick’s drama Blood Diamond, whose trailer is worth a viewing if only to listen to star Leonardo DiCaprio’s patently ridiculous South African accent. He’s really trying much too hard. Apparently, the movie expects us to believe that the struggle to control an ultra-rare pink diamond is reason enough for two hours of running, shouting, and exploding. Poor Djimon Hounsou’s talents are being wasted here, by the looks of things. Decide for yourself here.

Finally, there’s the odd one of the bunch, “historical adaptation” The Nativity Story. Aside from a cryptic teaser that showed us no actual footage, little was known about the film until the full trailer’s release yesterday. Having watched it now, I can only say: what a disappointment. Looking not remotely cinematic–more like a poorly-lit home movie, in fact–it appears to be a completely conventional depiction of the events surrounding Christ’s birth as depicted in Matthew. In short, it’s boring.

Keisha Castle-Hughes, best known as the youngest-ever Best Actress nominee (for Whale Rider), fills in as Mary and Oscar Isaac (of Syriana) for Joseph, while Ciaran Hinds and Shohreh Agdashloo, both capable actors, provide supporting roles (as Herod and, uh, someone else). Notice the message at the end of the trailer: New Line is clearly going after the church groups that helped make The Passion such an outsized success. But don’t take my word for it; the trailer, such as it is, can be found here.

–D. S. W.